Navigating Neurodivergence: Cultural Humility & Compassion

A Reflection on Power, Inclusivity, and Strength in Mental Health

As someone who self-identifies as ADHD (with Autistic traits) and as someone working in the mental health field, I have recently found myself reflecting on how neurodivergent people (particularly those who are Autistic, ADHD or AuADHD) are often required to navigate a world that is largely built on neurotypical rules and expectations. Many of us in our day-to-day lives may not stop to really consider that society has a set of default norms that we simply may not realise. But the truth is, these can sometimes create significant challenges for neurodivergent individuals.

In particular, I have been considering how these challenges are not only personal but are also deeply embedded in our systemic power dynamics. This morning, I took part in a Professional Development session called Counselling Autistic Adults: Understanding the Complexity of the Autistic Experience (facilitated by Jacqueline Gibbs - NDATS). Not only did this session invite me to consider some of the nuances of the autistic experience, but it also led me to reflect more broadly on how neurodivergence intersects with mental health care. I have been interested in this intersection for a while, particularly as I have worked with some neurodivergent (ND) clients who have been negatively impacted by the current mental health care system. For example, I am currently working with a client to navigate their trauma around their past (and ongoing) experiences with mental and medical health professionals. They feel that they have been mistreated within the medical and mental health systems due to a lack of training and understanding around neurodiversity in the field, which in turn has led to significant distress and a deep mistrust of the system.

In this blog article, my aim is to explore how power differentials in therapy, the need for cultural humility in practice, and the importance of challenging deficit-based narratives can collectively contribute to a more inclusive and neurodivergent-affirming approach in the mental health field.

Power Differentials in Mental Health: Navigating the Therapist-Client Relationship

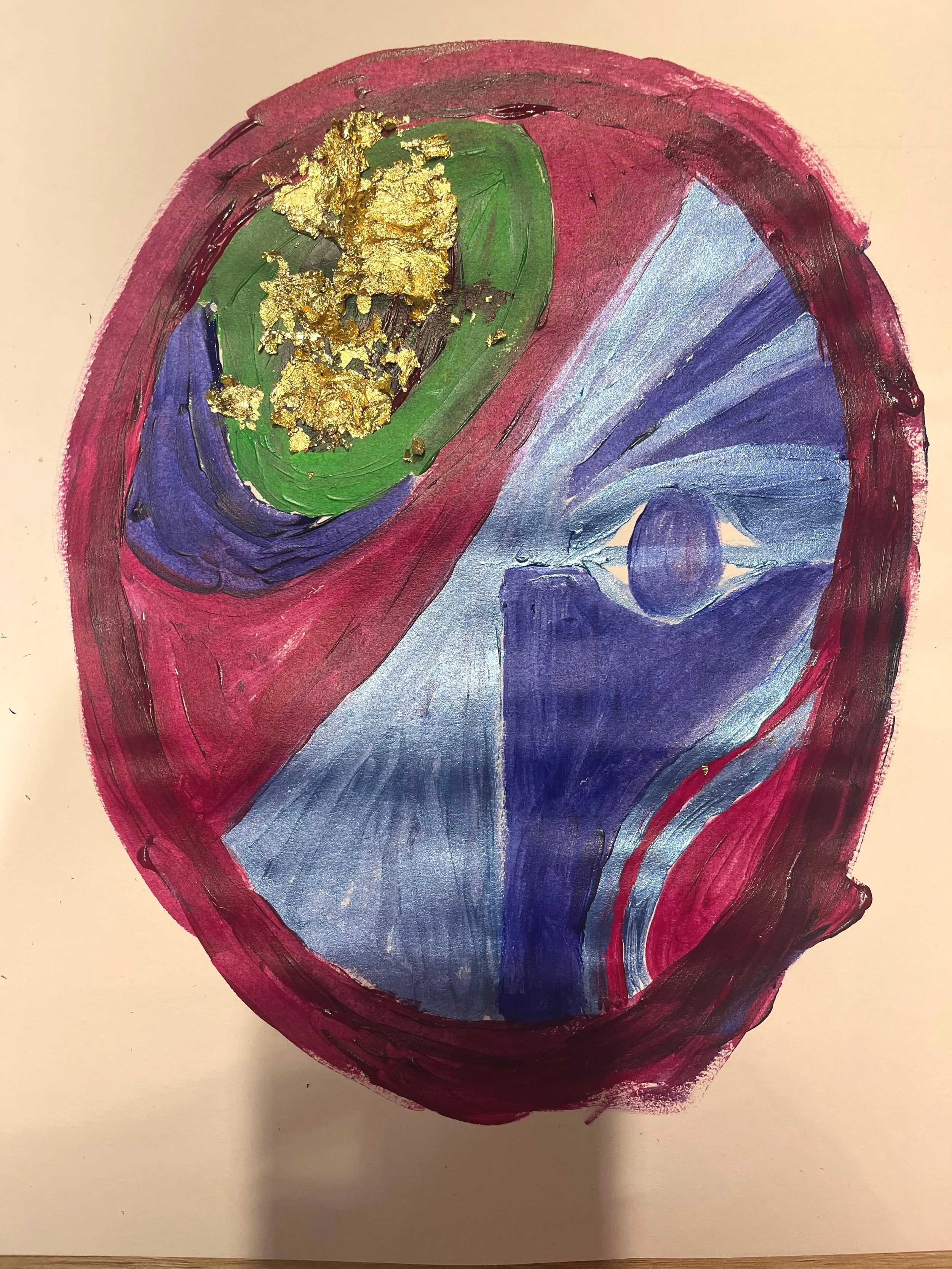

Figure 1: Briony Tronson, Mask-Inner and Outer Self, 2022, Paint & Gold Leaf on Paper.

A reflection on masking, considering how we may present ourselves externally compared to how we feel internally

As a therapist, one of the most striking realisations I have had in recent years is the potential power differential that can exist between neurodivergent clients and neurotypical therapists. This imbalance may not always be visible or explicit, but it can certainly be felt in how therapy may be structured and in the unspoken expectations that clients may feel pressured to conform to. Recognising and understanding these dynamics is an essential key to creating a more authentic and supportive space for clients who are neurodivergent

Our mental health care system still essentially works within the constructs of the medical model of care- and as such, it is healthy to at least acknowledge that most therapists are trained to understand and work within these more neurotypical frameworks. When we consider these frameworks and how they translate to practice, it makes sense that this has the potential to be problematic for neurodivergent, as they may feel pressured to adjust to these frameworks, often at the cost of their authenticity. This pressure can lead to ‘masking’, a phenomenon where neurodivergent individuals suppress their natural behaviours in order to fit in (e.g. in social situations, within health contexts, the workplace etc…)

For example, a therapist may expect eye contact from a client or a specific facial expression to accompany an emotion, or for the client to remain seated, but may not consider that these behaviours may not be how the ND client’s neurotype typically expresses itself. When a client’s nervous system is activated, they may also ‘stim’- which can include behaviours such as hand flapping, rocking or repetitive speech. To the casual viewer, these behaviours may seem out of context, but they are very important to the person behaving this way, as they are neurobiological ways to manage emotional regulation and sensory input. When therapists overlook or dismiss stimming (or even actively discourage it), this can increase pressure for the client to mask, ultimately preventing clients from engaging in actions that help them manage sensory overload or emotional distress.

Research by Damien Milton (2012) on the concept of neurodiversity highlights that ‘masking’ can be an exhausting and damaging experience for neurodivergent individuals, as it involves continuously suppressing one’s authentic self to conform to societal expectations (Milton, 2012). This masking is often reinforced by societal norms that do not recognise neurodivergent ways of being, and the constant effort can lead to emotional burnout, anxiety and diminished self-esteem.

This often unrecognised expectation for clients to behave in a particular way can be invalidating and lead to feelings of inadequacy or frustration- particularly when they may already struggle with these norms. For example, it can be a deeply invalidating experience to be told, there “must be something wrong with you because meditation universally works for people." I often hear this type of example from ND individuals, where they are told that a specific strategy ‘should’ work, yet it doesn’t because it fails to acknowledge their unique neurotype. Not only is this invalidating, but can damage trust within the therapeutic relationship.

For me, it is becoming increasingly clear that we must acknowledge and actively work to dismantle these power dynamics- so that we do not perpetuate trauma. This means creating an affirming and non-judgmental space where neurodivergent clients can express themselves authentically, without the pressure to ‘fit in’ with neurotypical expectations. By doing this, we can begin to create an environment where trust and meaningful therapeutic relationships are possible. Cultural humility enables us to begin dismantling the walls of power that often invalidate neurodivergent identities. By doing this we can deepen the therapeutic process.

But understanding power dynamics is just one piece of the puzzle. As we acknowledge these disparities, it makes sense that the next step should be about embracing cultural humility. This allows us to challenge these dynamics and create an inclusive therapeutic space

Cultural Humility and Inclusivity in Therapy

Figure 2: Briony Tronson, Parts of Self, 2022. Different parts of self - which are multifacted and complex. I find some parts of myself feel different or shameful. I often suppress these parts to fit societal norms.

Right now, as mental health professionals within our respective fields, we have the opportunity to learn how to approach neurodivergent individuals with cultural humility. But this extends way beyond cultural awareness- it also needs to encompass active listening, learning, and openness to understanding the lived experiences of others. A term I heard this morning, which I quite liked, is “cultural competemility”- which in essence is a mix of compassion and humility. It is a willingness to understand and respect the lived experiences and unique ways of being that neurodivergent individuals bring to the table. This means moving beyond assumptions and embracing the diversity of neurodivergent experiences.

When we consider cultural humility in therapy it is clear that it needs to involve more than just ‘awareness’. It is one thing to be ‘aware’ and quite another to move this into action. Cultural humility in ‘action’, is about actively listening and adapting our approach to meet the specific needs of neurodivergent clients. To truly embrace ‘inclusivity’ requires us to acknowledge that Autistic and other ND individuals can have different ways of communicating, processing emotions and interacting with the world. This is often in ways that are valid and functional for them and can help support their nervous systems in ways we may not be able to see.

Neurodivergence is not monolithic. Neurodivergence encompasses a vast spectrum of cognitive styles and experiences. When considering how to work with neurodivergent individuals, it is important to acknowledge how ND clients may experience and process the world. For example, those with Autistic traits may experience more rigid, structured thought patterns (often aligned with Autistic traits), whilst those with ADHD others may experience more fluid, non-linear thinking. Neurodivergence is complex and diverse and this really highlights the importance of our therapeutic approaches being tailored to meet the unique needs of every client. For example, one neurodivergent client may thrive in a more structured environment (possibly allowing for a greater sense of safety and comfort in predictability), whereas another clients may need greater flexibility and freedom to explore ideas without rigid boundaries. Honouring a person-centred, collaborative therapeutic relationship- this should also, always be explored with each client.

The ‘intersectionality’ of neurodivergence with other identities, including race, gender, and sexuality is also essential to consider within our therapeutic work. Intersectionality recognises that we all bring along our own personal values, interests and beliefs based on our lived experience. Each of us is an individual with unique identities, and each of us can experience discrimination and oppression depending on these overlapping identities. So, for example if we were to consider a LGBTQIA+ neurodivergent client, we may find they experience discrimination both because of their neurodivergence as well as their sexual/gender identity, while a BIPOC neurodivergent client may face added barriers due to cultural stigma It is also important for us as clinicians to keep a check on our own privileges and biases. By practising cultural humility within the mental health fields, we can help avoid unintentional bias and microaggressions, especially when these identities intersect.

Some ways to create an inclusive therapeutic space:

Be explicit and clear in communication- acknowledge that neurodivergent individuals may need more time or different types of support to process information.

Respect sensory sensitivities and adjust the environment or therapeutic approach when necessary (e.g. lower lights, offer breaks or adapt the pacing of sessions).

Cultivate safety and authenticity by encouraging clients to express themselves without the need to mask or hide their natural behaviours/processing styles.

Help support clients in their preferred communication styles, whether this be verbal or non-verbal. This might be through alternative means (e.g. art, writing or movement).

Adapt to cognitive styles: Acknowledge that some clients may prefer and thrive in more structured environments, whilst others may require more flexibility. By tailoring our approach we can help foster a more inclusive space.

These steps are not one-size-fits-all solutions but can be a good place to begin in considering how we can incorporate a collaborative and adaptable approach within our practice- deeply respecting the neurodivergent client’s needs and preferences.

Figure 3: Briony Tronson, Wool & Felt, 2024 . Some beautiful sensory-affirming materials. Sometimes, different textures can provide comfort and safety to clients. In our practices it is important to consider sensory accommodations for neurodivergent individuals, in order for them to express themselves fully.

Challenging the Deficit-Based Narrative: Neurodivergence as Strength

One of the most harmful ways western society perceives neurodivergence is through a deficit-based perspective. This viewpoint considers neurodivergent individuals as ‘lacking’ in certain areas, such as social understanding, organisation, or emotional regulation, and the common default assumption that something needs to be ‘fixed’ or ‘corrected’.

It is interesting to consider, however, that when we consider neurodivergence through a neuro-affirming lens, we can begin to recognise that neurodivergent individuals bring unique perspectives and strengths to the world. For example, autistic individuals may excel in creative problem-solving, attention to detail or be able to deeply focus on specific interest areas, which can potentially lead to expertise. Similarly, people with ADHD often possess remarkable energy, creativity and the ability to think outside the box- skills which are increasingly valued within business, creative industries and entrepreneurship.

Recognising these strengths is crucial in shifting the conversation around neurodivergence from a focus on deficits to one of diversity. By changing our perspective, we can begin to foster a greater recognition that neurodivergent individuals contribute to society in meaningful ways and that their unique traits can be seen as strengths rather than obstacles to perceived ‘normalcy.’

Rather than focusing solely on challenges and/or behaviours that don't conform to neurotypical norms, we can help clients leverage their strengths and develop coping strategies that align with their neurotype and how it manifests in the world. This shift encourages a much more empowering and affirming therapeutic experience and one that honours the neurodivergent client’s authentic self. I know for one, I really value a ‘strength-based’ approach to therapy within my practice.

Conclusion: Moving Toward a Neurodivergent-Affirming Practice

Neurodivergent clients, like all people, have a unique way of being in the world. To create a truly affirming therapeutic space where neurodivergent clients feel seen, heard, and respected, we must first acknowledge the power dynamics in the therapeutic relationship, challenge deficit-based narratives, and adopt a cultural humility approach. This is how we create inclusive spaces, and this is how we can provide more effective mental health care.

At its core, it is about shifting the lens through which we view neurodivergence, moving from a medical, deficit-based model to one that affirms and celebrates neurodiversity. I am aware this is just one perspective, but I do believe that ongoing reflection and remembering just how unique we all are as humans is vital to our learning. If we could all just bring a little more ‘cultural competemility’ into our practice, I believe we can contribute to a more inclusive, compassionate mental health field, one where neurodivergent individuals can better thrive within their lives.

Acknowledgments:

With thanks to this mornings PD session, “Counselling Autistic Adults: Understanding the Complexity of the Autistic Experience,” facilitated by Jacqueline Gibbs (NDATS), for inspiring my reflections on cultural humility and compassion in therapy.

I would also like to acknowledge the collaborative support of AI (ChatGPT), which played an important role in organising, clarifying and refining my thoughts while writing this article- which may I say I find particularly useful as someone with an ADHD brain! Ethical transparency in the use of technology is important to me, and I believe it is essential to recognise AI’s contribution in this process openly.

If you would like to read more thoughts around my use of AI in a more creative sense, please visit: https://www.liminalwilds.com.au/ai-aknowledgment.

References:

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the 'double empathy problem'. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887